Lower Engadin Culture.

Engadin Houses & Sgraffiti

The Engadin House

Typical of the Engadin house are the massive stone walls, often decorated with sgraffito, the deep windows, the bay window and the two entrance gates in the sulèr and the stable at the front. The Engadin house is rarely perceived as a stand-alone building, but is usually associated with the neighbouring houses. When the Engadin villages were razed to the ground in various wars and then rebuilt, the houses moved ever closer together. The villages were built as close together as possible in order to be better able to defend themselves and have more security. Since then, the individual houses have stood facing each other around small squares with fountains in the centre. They face the village square or the street and not the sun.

The structure

The house consists of a residential part and a farm part (stable, barn), which are situated one behind the other. The farm part with the hayloft is usually south-facing so that the hay can dry well and thus prevent hayloft fires. The typical vertical wooden walls are fitted with ventilation slits to ensure good aeration of the hay. The massive-looking stone houses are usually wooden houses at their core. The walls, built from wooden beams, were only cladded after the wood had dried. Their thickness can be recognised by the deep, funnel-shaped window recesses.

Historic houses

The most beautiful sgraffito villages in the Engadin

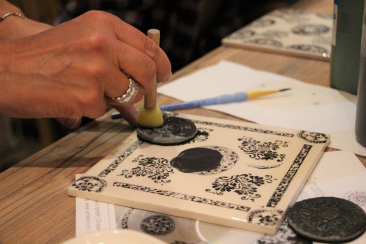

Engadin houses are famous for their house paintings and sgraffito ornaments. Originally, master builders from Italy brought the scratching technique - known as sgraffito for short - to Graubünden in the 16th century. Later, local craftsmen also learnt the skills, transforming many a nondescript village into a real gem over the course of time. Scraped plaster experienced its heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries, after which the decorative elements disappeared again, mostly in the course of remodelling or renovations. As richly decorated buildings attracted thieves even back then, some house owners simply painted over the scratched drawings to avoid creating false incentives. They were rediscovered at the end of the 19th century as an element of the Grisons local style.

Mysterious symbols.

Understanding sgraffiti

The protective and lucky signs on the house facades have different meanings. The houses are decorated with geometric shapes, but also with mystical figures and symbols such as dragons, fish and mermaids.